#john donne biography

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

spurred by seeing the st. lucie's day poem: one of my all-time favourite literary biographies is katherine rundell's "super-infinite: the transformations of john donne," which is illuminating, funny, well-written in its own right, and brimming with genuine love for its subject. highly recommended for anyone who wants to read more about donne or just generally wants to have a good time

it's on my wishlist, so this should be what i need to actually get it!

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

9 books I plan to read in 2025

Tagged by @aeide 🖤

Meant to do this sooner, but, well, life... 🙃

Most of these are non-fiction because I have to be in the right mood to read fiction. And they're all books on my shelves because I should probably actually get to those first before borrowing anything more from the library... Therefore, have pictures:

Don't know who has or hasn't been tagged in this, so if you see this post, congrats. You've been tagged. What are 9 books you want to read in 2025?

No, you don't need to take photos, I just felt like it.

Proper list (and more pictures of books) below 👇

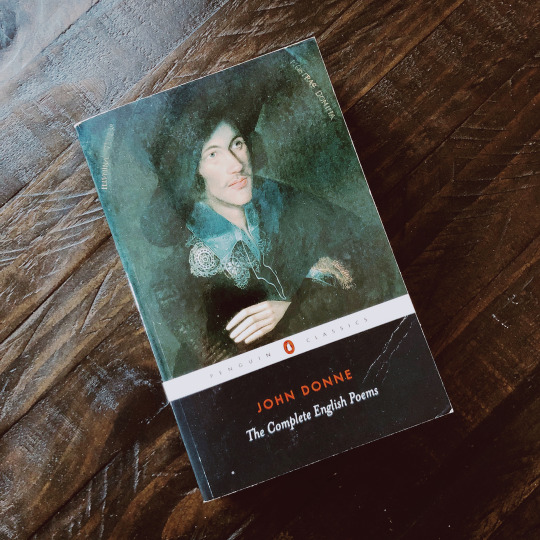

The Complete English Poems - John Donne

Someone has been very slowly chipping away at this for ages and should probably actually finish it one day...

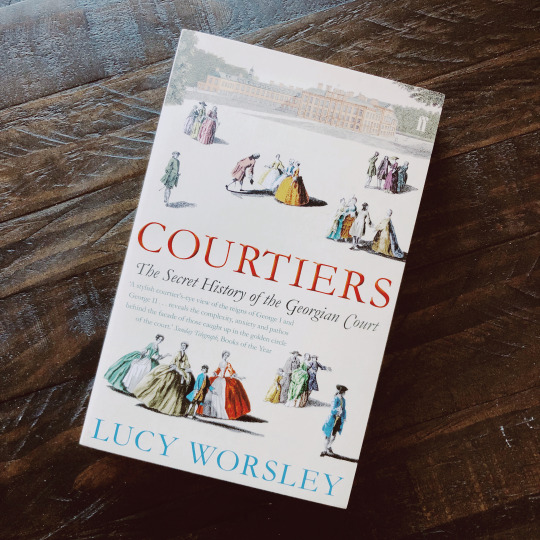

2. Courtiers: The Secret History of the Georgian Court - Lucy Worsley

I don't think anyone following my blog should be surprised I like 18th Century history? And this one has also been sitting on the shelf for a while now...

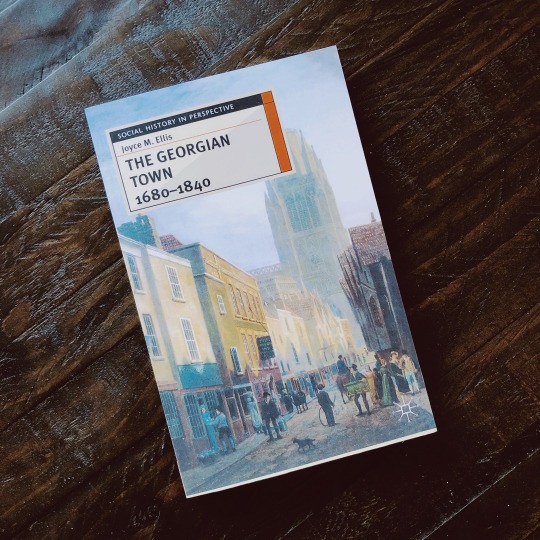

3. The Georgian Town 1680-1840 - Joyce M. Ellis

Recent Christmas gift. Again, 18th Century history, or, more specifically, the Long 18th Century, covering the end of the 17th and beginning of the 19th Centuries as well. Fairly small book, too, so possibly a quicker read?

4. Sense and Sensibility - Jane Austen

My dad bought me this edition when the family was in Rome. And I'm due for a re-read anyways...

5. the Last Witches of England: A Tragedy of Sorcery and Superstition - John Callow

As well as reading about the 18th Century a fair bit, I also like reading about witch trials, the belief in witchcraft and magic, occult history... This is another Christmas gift that I should get to before it sits too long on my shelves like other books.

6. Jane Austen at Home: A Biography - Lucy Worsley

Another Worsley book I've had sitting on the shelves a bit too long. And, of course, some more Georgian/Long 18th Century history.

7. The Book of Magic: From Antiquity to the Enlightenment - Brian Copenhaver

A book with a series of excerpts that mention magic/witchcraft/witch trials/occult history, from the bible to the Greek Magical Papyri to mentions of magic in literature from the likes of Shakespeare and Spencer. Once again, it's been sitting on the shelves for a bit... (It's a little long and dense.)

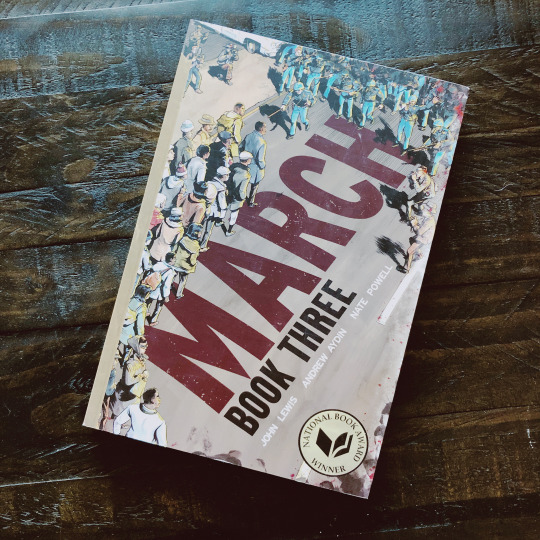

8. March: Book Three - John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, Nate Powell

Have obviously already read the first two books of the March series. Honestly think graphic novels are an excellent way to tell stories like these. And all three are very much worth picking up. Will probably be reading this relatively soon.

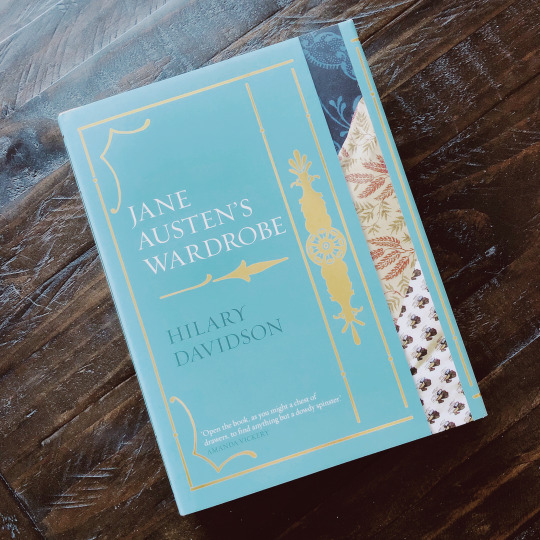

9. Jane Austen's Wardrobe - Hilary Davidson

More Jane Austen? More Regency/Georgian history? Shocking. But yes, would like to get to this soon. Hilary Davidson's other book, Dress in the Age of Jane Austen, was very good, and I recommend picking it up if this sort of thing interests you.

#books#tag#book#reading#tbr#to be read#booklr#bookblr#history#nonfiction#non fiction#fiction#poetry#graphic novel#classics

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi jem tbis is random but I'm reading a really bad book today (it's so fun) n now I'm like thinking ab books so. what r some books u love?:0 im goinf 2 steal recs from u

HI YES SORRY I TOOK A WHILE TO ANSWER BUT I DO HAVE RECS OF VARYING STYLES SO YOU CAN PICK WHATEVER APPEALS

all the crooked saints by maggie stiefvater (if you read anything from the list make it this book. oh my god. i dont think i can describe it but its incredible and funny and warm and utterly unique and stiefvaters writing style is wonderful. magical realism and weird christianity (?) stuff going on. like a fever dream except not really.)

melmoth by sarah perry (supernatural gothic novel published in 2022 and playing VERY heavily on gothic tropes; stunningly written but a heavy read so dont pick it unless youre in the right headspace to cry your eyes out over various horrifying atrocities)

the well of loneliness by radclyffe hall (a lesbian novel written in the 1920s in which the main character can very clearly be interpreted as transmasc!! the reason for this is that its based on the karl heinrich ulrich theory of sexology which suggests that gay love is natural because gay men are just female psyches in male bodies but its still a very interesting novel and radclyffe hall was herself wlw and gnc. the prose style reads like it was written 30 years before it actually was and often the characters are melodramatic and insufferable but its wonderful anyway)

rebecca by daphne du maurier (SO GOOD. modern gothic & ghostly but with a psychological spin)

the his dark materials series by philip pullman (i dont even know what to say about this one. shaped me as a person. themes of christianity and the church. objectively incredible series)

david copperfield by charles dickens (so so charming and wonderfully written. took me like a month to read. my fav dickens is still a tale of two cities but this one is more light-hearted.)

super-infinite by katherine rundell (JOHN DONNE BIOGRAPHY!!!! but its so enchanting and warm and honestly not at all difficult to read like its barely non-fiction. rundell is a childrens author who wrote some of my fav books when i was younger and you can really feel that lovely writing style in this biography)

a fatal thing happened on the way to the forum by emma southon (non-fiction book about ancient roman attitudes to murder!! SO funny and easy to read and genuinely gripping and while it deals with specific subject matter it still gives you a pretty good understanding of the entirety of roman history which is pretty good)

um yeah i think thats it <3

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Analyzing "Batter my heart, three-person'd God" through an Oppenheimer-ian lens

Physicist and Manhattan Project leader J. Robert Oppenheimer named the test of the first atomic bomb "Trinity." He claimed he was inspired by John Donne's poem "Batter my heart, three-person'd God," but offered little other explanation. Below is my reading of the poem and how it can be applied to Oppenheimer's life.

You can read the poem here.

Batter my heart, three-person'd God

Oppenheimer is the first-person narrator of this poem, aka the one whose heart is being battered. The three-person'd God is composed of, well, three concepts: America, the atomic bomb, and science (which in and of itself can be three-pronged into what's oft considered the most prestigious sciences: biology, chemistry, and physics). These three "persons" were the most defining forces in Oppenheimer's life.

for you / As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;

The purpose of science is to knock on the door of discovery, breathe life and shine light into the unknown, and use this newfound knowledge to seek to mend our world—to make it a better place. True love is being understood, after all, and when we understand the world, we grow to love and appreciate it.

From an American prespective, the bomb also sought to mend. Its purpose was to end World War II, which it ultimately succeeded in doing. The first three verbs could also be used to describe the sound, movement, and appearance of the Trinity explosion.

Post-war American foreign policy could also be categorized as seeking to mend. Once again, from an American prespective, it was the country's role to shine democracy and freedom into the dark, communist-threatened corners of the world. To "fix" them. But we all know how that turned out.

That I may rise and stand,

The American government made Oppenheimer the head of the Manhattan Project, which, by several accounts, inflated his ego with a sense of leadership and control. As the fictionalized version of Atomic Energy Commission chairman Lewis Strauss says in Christopher Nolan's 2023 film Oppenheimer:

"Well, if he was based in Chicago, he worked under Szilard and Fermi, not the Cult of Oppie in Los Alamos. Robert built that damn place. He was founder, mayor, sheriff. All rolled into one."

Harnessing the extraordinary power of atomic energy also made Oppenheimer feel godlike, a Prometheus figure, as the biography title goes. Physicist and professor Philip Morrison put it bluntly:

"Oppenheimer think's he's God."

o'erthrow me, and bend / Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.

Ultimately, however, the power of atomic energy won the power struggle. Oppenheimer is forever its slave, the consequences of its unleashing dictating the rest of his life. He is transformed, made into a new person when the Trinity explosion breaks, blows, and burns ahead in the horizon.

(The "me" who is made new could also the be the world, which is also forever changed by the creation of the atomic bomb).

Although I have less faith in this argument, these lines could also be applied to the Atomic Energy Commission's kangaroo court purge of Oppenheimer. After the trial, he was absolutely broken, overthrown from his position on the Commission, his influence on atomic policy. He was never quite the same afterwards; made new.

I, like an usurp'd town to another due,

The most overt interpretation of this line would be that Hiroshima and Nagasaki are the usurp'd towns in question, destroyed by what were arguably war crimes. However, Los Alamos could also the be usurp'd town: it was a region sacred to Native Americans that was seized by the US government for the Manhattan Project, at Oppenheimer's reccomendation. The National Park Service explains:

"In late 1942, the U.S. government appropriated US Forest Service land and private property on the Pajarito Plateau for its secret atom bomb project. The US government subsequently built fences and established checkpoints to prevent any unauthorized entries by the public and that barred American Indians and former landowners from returning."

Labor to admit you, but oh, to no end;

As will be discussed later, Oppenheimer felt more distress over the nuclear proliferation and atomic culture that rapidly developed post-war, rather than the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He labored to admit the bomb into standard military arsenals and into the world overall, but both the US and the USSR were building bomb after bomb. The proliferation was to no end; it defined 45 years of the 20th century.

Reason, your viceroy in me, me should defend, / But is captiv'd, and proves weak or untrue.

As the so-called father of the atomic bomb, Oppenheimer should defend its existence and the actions of the US government in its proliferation. By extension, he should defend the development of the hydrogen bomb. However, Oppenheimer cannot find a logical or moral basis for defense. His criticism and campaign against the H-bomb partially leads to the Atomic Energy Commission's takedown of him.

Yet dearly I love you, and would be lov'd fain, / But am betroth'd unto your enemy;

The most overt interpretation of this line would be that the "you" in question is America. Oppenheimer's country would love him if he wasn't a suspected Communist; instead, he faces the wrath and persecution of the Atomic Energy Commission.

From the film:

EINSTEIN: If this is the reward [your country] offers you, then... perhaps you should turn your back on her.

OPPENHEIMER: Damnit, I happen to love this country.

EINSTEIN: Then tell [the Commission] to go to hell.

However, "you" could also be science, perhaps physics specifically. The atomic bomb is the antithesis of the purpose of science outlined above. As physicist Isidor Rabi said:

"I do not wish to make the culmination of three centuries of physics a weapon of mass destruction."

And as Oppenheimer reflected:

"I find that physics and the teaching of physics, which is my life, now seems irrelevant."

How can Oppenheimer be a servant to the sciences when he has defied them? He struggles to find passion and meaning in his field; he is now devoted to lessening the effects of its corruption.

Finally, "you" could also be the bomb. Oppenheimer hated nuclear proliferation, not the bombings during World War II. He was certainly proud of his creation, but regretted its consequences. Many believed Oppenheimer loved the bomb because of the status it gained him. Another film Lewis Strauss line:

“Oppenheimer wanted to own the atomic bomb. He wanted to be the man who moved the Earth. He talks about putting the nuclear genie back in the bottle. Well I'm here to tell you that I know J. Robert Oppenheimer, and if he could do it all over, he'd do it all the same. You know he's never once said that he regrets Hiroshima? He'd do it all over. Why? Because it made him the most important man who ever lived.”

One could say the ultimate goal of the bomb is a nuclear holocaust, the destruction of the human race by a creation of the human race. Thus, in his pursuit against proliferation, Oppenheimer is the enemy of the bomb.

Divorce me, untie or break that knot again, / Take me to you, imprison me, for I, / Except you enthrall me, never shall be free,

Oppenheimer can never escape the consequences of his actions. They haunt him, define him, and destroy him, whether from internal or external forces. He never shall be free as long as the bomb enthralls him. He tries to avenge his sin by advocating against proliferation and the H-bomb, but his influence is plowed over by the Atomic Energy Commission. This strips him of his ability to work his way out of purgatory. He is a permanent prisoner to the bomb, as all humans are as long as we live under its threat.

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

Oppenheimer is ultimately destroyed by his country and the consequences of his actions. They ravish him and leave him chained to the rock, à la Prometheus.

Fin.

To reward yourself for making it this far, I recommend checking out Gerald Finley's performance of "Batter my heart" from John Adams's opera Doctor Atomic.

Thanks for reading!

#oppenheimer#j robert oppenheimer#history#american history#atomic bomb#oppenheimer movie#poetry#poem#poetry analysis#writing#john donne#cillian murphy#christopher nolan#gerald finley#john adams#united states#united states history

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

4, 9 and 12 for the book meme game? :-)

Dd you discover any new authors that you love this year?

I read Emily Zhou's debut collection, Girlfriends, and REALLY enjoyed it! 'Contemporary short stories that are mostly dialogue' is a form I enjoy when pulled off well but for which I have a high bar before I will say it was pulled of well, and the stories in that collection all landed for me in that sense, which is impressive. I also loved the novel I read from Anya Johanna DeNiro, OKPsyche, and immediately went and either read other work by her or added it to my to-read list. Both writers I will be keeping an eye out for new releases from in the future. I also read Eka Kurniawan after meaning to get around to him last year, and while his short story collection was more hit-or-miss, the novel of his I read (Man Tiger) really impressed me.

Did you get into any new genres?

One kind of nonfiction I very rarely read is longform biography, but this year I read one so damn good (Super-Infinite: the Transformations of John Donne) that it inspired me to try, next year, to read some more of those. I'm gonna be prowling around looking for stuff in the same vein. It was a total surprise to me how much I enjoyed it.

Any books that disappointed you?

I really wanted to like Transland: Consent, Kink and Pleasure. I really really did. A book looking at kink through the lens of trans experience is an easy sell for me. Unfortunately it is quite poorly written, has very little interesting to say about its topic for most of the time, and also goes some strangely conservative places in a way that feels totally unselfaware, including around gender and transness. Actually, I think I should go drop the rating on storygraph tbh, now I'm thinking about it, that book was such a letdown.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books of 2024 - August, September and October

Still struggling to read consistently, mainly due to mental health and personal circumstances at the moment... But I have managed to finish some books over the last few months (although, I haven't finished anything this month yet 👀) and here they are:

August

Emma by Jane Austen - I have nothing left to say about this other than it's my favourite and I'm depressed so... 🤷♀️

Summer by Edith Wharton - I don't really remember this 3 months later but it was probably fine? I just remember thinking this hadn't aged very well

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke - I buddy read this with my best friend and I loved it even more the second time around.

Harry Potter 1 & 2 - depression set in and I listened to these in bed because I couldn't face anything else...

September

Harry Potter 3 & 4 - same as above

Morality Play by Barry Unsworth - objectively this book is excellent, not perfect but very good. The writing is superb, but I definitely read it at the wrong time and I didn't enjoy it as much as I should have done on paper.

October

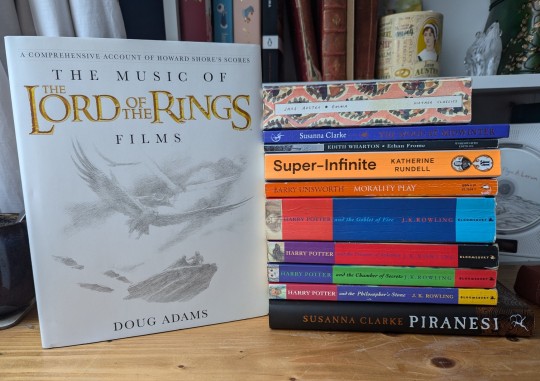

The Music of the Lord of the Ring Films by Doug Adams - very mixed feelings about this one. I enjoyed experiencing it, but I do think Adams missed out on writing a more interesting book. The first quarter was fantastic analysis on Shore's score and how it related to the films and Tolkien's writing. The last three quarters is far too descriptive of what each track does... I kept thinking I could hear this for myself and I didn't really need to read someone spelling it out to me? But I might know too much about music for this one. I really do want to write about this book separately because I have a lot of thoughts.

Super-Infinite: the Transformations of John Donne by Katherine Rundell - this is a fun piece of nonfiction writing! It sort of fails as a biography of John Donne because Donne is so elusive in history as an individual (despite being a giant of early modern English literary history). However, it's a fantastic history of the intellectual circles of the late Elizabethan and Jacobean period! Seriously it's so good at introducing someone to this complex and bizarre world and I'd highly recommend it for that!

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton - the book that taught me an excellent story can be ruined by ONE STUPID MOMENT...

The Wood at Midwinter by Susanna Clarke - the first miss for me from Clarke and you can read why here.

Still reading:

When Christ and His Saints Slept by Sharon Penman

Emma by Jane Austen (again)

Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke

#books of 2024#mini book reviews#august reads#september reads#october reads#I'm not tagging all of these#not proofread

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early in the morning of July 16, 1945, before the sun had risen over the northern edge of New Mexico’s Jornada Del Muerto desert, a new light—blindingly bright, hellacious, blasting a seam in the fabric of the known physical universe—appeared. The Trinity nuclear test, overseen by theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, had filled the predawn sky with fire, announcing the viability of the first proper nuclear weapon and the inauguration of the Atomic Era. According to Frank Oppenheimer, brother of the “Father of the Bomb,” Robert’s response to the test’s success was plain, even a bit curt: “I guess it worked.”

With time, a legend befitting the near-mythic occasion grew. Oppenheimer himself would later attest that the explosion brought to mind a verse from the Bhagavad Gita, the ancient Hindu scripture: “If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the mighty one.” Later, toward the end of his life, Oppenheimer plucked another passage from the Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Christopher Nolan’s epic, blockbuster biopic Oppenheimer prints the legend. As Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) gazes out over a black sky set aflame, he hears his own voice in his head: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” The line also appears earlier in the film, as a younger “Oppie” woos the sultry communist moll Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh). She pulls a copy of the Bhagavad Gita from her lover’s bookshelf. He tells her he’s been learning how to read Sanskrit. She challenges him to translate a random passage on the spot. Sure enough: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” (That the line comes in a postcoital revery—a state of bliss the French call la petite mort, “the little death”—and amid a longer conversation about the new science of Freudian psychoanalysis—is about as close to a joke as Oppenheimer gets.)

As framed by Nolan, who also wrote the screenplay, Oppenheimer's cursory knowledge of Sanskrit, and Hindu religious tradition, is little more than another of his many eccentricities. After all, this is a guy who took the “Trinity” name from a John Donne poem; who brags about reading all three volumes of Marx’s Das Kapital (in the original German, natch); and, according to Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s biography, American Prometheus, once taught himself Dutch to impress a girl. But Oppenheimer’s interest in Sanskrit, and the Gita, was more than just another idle hobby or party trick.

In American Prometheus, credited as the basis for Oppenheimer, Bird and Sherwin depict Oppenheimer as more seriously committed to this ancient text and the moral universe it conjures. They develop a resonant image, largely ignored in Nolan’s film. Yes, it’s got the quote. But little of the meaning behind it—a meaning that illuminates Oppenheimer’s own conception of the universe, of his place in it, and of his ethics, such as they were.

Composed sometime in the first millennium, the Bhagavad Gita (or “Song of God”) takes the form of a poetic dialog between a warrior-prince named Arjuna and his charioteer, the Hindu deity Krishna, in unassuming human form. On the cusp of a momentous battle, Arjuna refuses to engage in combat, renouncing the thought of “slaughtering my kin in war.” Throughout their lengthy back-and-forth (unfolding over some 700 stanzas), Krishna attempts to ease the prince’s moral dilemma by attuning him to the grander design of the universe, in which all living creatures are compelled to obey dharma, roughly translated as “virtue.” As a warrior, in a war, Krishna maintains that it is Arjuna’s dharma to serve, and fight; just as it is the sun’s dharma to shine and water’s dharma to slake the thirsty.

In the poem’s ostensible climax, Krishna reveals himself as Vishnu, Hinduism’s many-armed (and many-eyed and many-mouthed) supreme divinity; fearsome and magnificent, a “god of gods.” Arjuna, in an instant, comprehends the true nature of Vishnu and of the universe. It is a vast infinity, without beginning and end, in a constant process of destruction and rebirth. In such a mind-boggling, many-faced universe (a “multiverse,” in the contemporary blockbuster parlance), the ethics of an individual hardly matter, as this grand design repeats in accordance with its own cosmic dharma. Humbled and convinced, Arjuna takes up his bow. As recounted in American Prometheus, the story had a significant impact on Oppenheimer. He called it “the most beautiful philosophical song existing in any known tongue.” He praised his Sanskrit teacher for renewing his “feeling for the place of ethics.” He even christened his Chrysler Garuda, after the Hindu bird-deity who carries the Lord Vishnu. (That Oppenheimer seems to identify not with the morally conflicted Arjuna but with the Lord Vishnu himself may say something about his own sense of self-importance.)

“The Gita,” Bird and Sherwin write, “seemed to provide precisely the right philosophy.” Its prizing of dharma, and duty as a form of virtue, gave Oppenheimer’s anguished mind a form of calm. With its notion of both creation and destruction as divine acts, the Gita offered Oppenheimer a frame of making sense of (and, later, justifying) his own actions. It’s a key motivation in the life of a great scientist and theoretician, whose work was marshaled toward death. And it’s precisely the sort of idea Nolan rarely lets seep into his movies.

Nolan’s films—from the thriller Memento and his Batman trilogy to the sci-fi opera Interstellar and the time-reversal blockbuster Tenet—are ordered around puzzles and problem-solving. He establishes a dilemma, provides the “rules,” and then sets about solving that dilemma. For all his sci-fi high-mindedness, he allows very little room for questions of faith or belief. Nolan's cosmos is more like a complicated puzzle box. He has popularized a kind of sapio-cinema, which makes a virtue of intelligence without being itself highly intellectual.

At their best, his movies are genuinely clever in conceit and construct. The one-upping stage magicians of The Prestige, who go mad trying to best one another, are distinctly Nolanish figures. The tripartite structure of Dunkirk—which weaves together plot lines that unfold across distinct periods of time—is likewise inspired. At their worst, Nolan’s films collapse into ponderousness and pretension. The barely scrutable reality-distortion mechanics of Inception, Interstellar, and Tenet smack of hooey.

Oppenheimer seems similarly obsessed with problem-solving. First, Nolan sets up some challenges for himself. Such as: how to depict a subatomic fission reaction at Imax scale or, for that matter, how to make a biopic about a theoretical physicist as a broadly entertaining summer blockbuster. Then he sets to work. To his credit, Oppenheimer unfolds breathlessly and succeeds making dusty-seeming classroom conversations and chatty closed-door depositions play like the stuff of a taut, crowd-pleasing thriller. The cinematography, at both a subatomic and megaton scale, is also genuinely impressive. But Nolan misses the deeper metaphysics undergirding the drama.

The movie depicts Murphy’s Oppenheimer more as a methodical scientist. Oppenheimer, the man, was a deep and radical thinker whose mind was grounded by the mystical, the metaphysical, and the esoteric. A film like Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life shows that it is possible to depict these sort of higher-minded ideas at the grand, blockbuster scale, but it’s almost as if they don’t even occur to Nolan. One might, charitably, claim that his film’s time-jumping structure reflects the Gita’s notion of time itself as nonlinear. But Nolan’s reshuffling of the story’s chronology seems more born of a showman’s instinct to save his big bang for a climax. When the bomb does go off, and its torrents of fire fill the gigantic Imax screen, there’s no sense that the Lord Vishnu, the mighty one, is being revealed in that “radiance of a thousand suns.” It’s just a big explosion. Nolan is ultimately a journeyman technician, and he maps that personality onto Oppenheimer. Reacting to the horrific, militarily unjustifiable bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima (which are never depicted on-screen), Murphy’s Oppenheimer calls them “technically successful.”

Judged against the life of its subject, Oppenheimer can feel like a bit of let down. It fails to comprehend the woolier, yet more substantial, worldview that animated Oppie’s life, work, and own moral torment. Weighed against Nolan’s own, more purely practical, ambitions, perhaps the best that can be said of Oppenheimer is that—to paraphrase the physicist’s actual reported comments, uttered at his moment of ascension to the status of godlike world-destroyer—it works. Successful, if only technically.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

In retrospect, a biography of John Donne might not have been the best choice for reading material when I'm already depressed.

#john donne#in my defense all I really knew about him was from DLS#and the flea poem and his child bride#but I guess I could have predicted the Plague would come up#it's a good book though#Super-Infinite by Katherine Rundell#will finish it...and some point

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Holy Sonnet 10" by John Donne

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;

For those whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be,

Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee do go,

Rest of their bones, and souls’ delivery.

Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell,

And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well

And better than thy stroke; why swell’st thou then?

One short sleep past, we wake eternally

And Death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.

---

Brief Biography of John Donne

John Donne (1572–1631) was an English poet, priest, and cleric in the Church of England, famous for his metaphysical poetry. His works explore themes of love, religion, and death, often using complex metaphors and intellectual argumentation. "Holy Sonnet 10", also known as "Death, be not proud", is part of his religious poetry and challenges the power of death, asserting that death is not as fearsome as it seems. Donne's poetry and sermons were influential in the English Renaissance, and he is regarded as one of the greatest poets in the English language.

0 notes

Text

Hommage à Martial Solal (1927-2024)

Hommage à Martial Solal (1927-2024).Téléchargement des meilleures partitions dans notre bibliothèque.BiographieJeunesseBest Sheet Music download from our Library.Débuts professionnelsPlease, subscribe to our Library.StyleDiscographieBrowse in the Library:

Hommage à Martial Solal (1927-2024).

Martial Solal, né le 23 août 1927 à Alger (Algérie française) et mort le 12 décembre 2024 à Chatou (Yvelines), est un pianiste, compositeur, arrangeur et chef d'orchestre de jazz français. Sa carrière débute dans les années 1950, durant lesquelles il enregistre notamment avec Django Reinhardt et Sidney Bechet. Au Club Saint-Germain, il accompagne les plus grands musiciens américains de l'époque : Don Byas, Clifford Brown, Dizzy Gillespie, Stan Getz et Sonny Rollins. Il a enregistré plus d'une centaine de disques en solo, en trio ou avec différents big bands, ainsi qu'en duo - formule qu'il affectionne particulièrement -, avec entre autres Lee Konitz, Michel Portal, Didier Lockwood, John Lewis et David Liebman. Solal ne se limite pas à la scène jazz : il écrit de nombreuses œuvres symphoniques jouées notamment par le nouvel orchestre philharmonique, l'Orchestre national de France ou l'Orchestre Poitou-Charentes. Il compose également plusieurs musiques de films, notamment pour Jean-Luc Godard (À bout de souffle) ou pour Jean-Pierre Melville (Léon Morin, curé). Le style de Martial Solal, virtuose, original, inventif et plein d'humour, repose notamment sur un talent d'improvisation exceptionnel servi par une technique impeccable qu'il entretient par un travail systématique tout au long de sa carrière. Bien qu'il n'ait eu qu'un seul véritable élève en la personne de Manuel Rocheman, il a influencé de nombreux musiciens tels que Jean-Michel Pilc, Baptiste Trotignon, Franck Avitabile, François Raulin et Stéphan Oliva. Le prestigieux concours de piano jazz Martial Solal, organisé de 1988 à 2010, porte son nom. Biographie Jeunesse Martial Saoul Cohen-Solal est né le 23 août 1927 à Alger, alors en Algérie française, dans une famille juive algérienne non pratiquante. Son père, algérien de naissance, était un modeste comptable, sa mère était originaire de Ténès. Il apprend les bases du piano auprès de sa mère, chanteuse d'opéra amateur, puis auprès de Madame Gharbi qui lui donne des cours de piano classique dès l'âge de six ans. Son talent d'improvisateur se révèle dès l'âge de dix ans, lors d'une audition, lorsqu'il modifie l'ordre des séquences d'une Rhapsodie de Liszt, sans hésitation et sans que personne ne s'en rende compte. Adolescent, il découvre le jazz et la liberté qu'il permet, aux côtés de Lucky Starway, saxophoniste multi-instrumentiste et chef d'orchestre local à Alger. Starway lui a présenté Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, Teddy Wilson et Benny Goodman. Solal prend des cours avec lui pendant deux ou trois ans, durant lesquels il fait la « pompe » : une basse à la main gauche, un accord à la main droite. Lucky Starway l'engage finalement dans son orchestre. À partir de 1942, les lois sur le statut des juifs du régime de Vichy, entrées en vigueur dans les colonies françaises, interdisent à Martial Solal, enfant de père juif, d'entrer à l'école. Il se consacre donc à la musique. Le débarquement allié en 1942 lui évite la déportation. Durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, alors qu'il effectuait son service militaire au Maroc, il joua dans les mess des soldats américains. Débuts professionnels Départ pour Paris Solal devient musicien professionnel en 1945, ce qui ne l'empêche pas d'enchaîner des petits boulots en parallèle. Les opportunités étant limitées à Alger pour un pianiste de jazz, il s'installe à Paris au début des années 1950, à l'âge de 22 ans, sans connaître personne. Après quelques semaines, il joue dans plusieurs orchestres de jazz, comme ceux de Noël Chiboust ou d'Aimé Barelli, contraints, pour des raisons économiques, de jouer du tango, du java, du paso doble ou des valses. Le Club Saint-GermainMartial Solal fréquente le Club Saint-Germain, alors le plus important en matière de jazz, et commence à y jouer en 1952. Il y sera le « pianiste maison » pendant une dizaine d'années, en alternance parfois avec le Blue Note, le autre grand club de jazz. Au Club Saint-Germain, avec le batteur Kenny Clarke et le bassiste Pierre Michelot, il accompagne des musiciens américains en visite, tels que Don Byas, Lucky Thompson, Clifford Brown, Dizzy Gillespie, Stan Getz et Sonny Rollins. Il y rencontre également André Previn, ainsi qu'Erroll Garner et John Lewis. En novembre 1954, il accompagne l'orchestre Barelli dans une tournée à travers la France et l'Afrique du Nord. Il crée un quatuor avec Roger Guérin à la trompette, Paul Rovère à la contrebasse et Daniel Humair à la batterie, et joue également du piano solo, dans un style inspiré d'Art Tatum. Entre 1959 et 1963, il accompagne avec son orchestre des chanteurs français tels que Line Renaud, Jean Poiret et Dick Rivers. En 1961, Solal compose la musique du tube Twist à Saint-Tropez. En 1956, Martial Solal crée son premier big band, salué par le compositeur — et ami de Martial Solal — André Hodeir. Dans son écriture, le piano alterne souvent avec l'orchestre, la section des saxophones est bien équilibrée, le jeu des trompettes est musclé. En 1957 et 1958, Solal enregistre d'autres titres avec son big band, tandis que son écriture se complexifie, avec un son plus massif et une tessiture plus large. Les changements de rythme et de tempo, qui deviennent alors sa signature, se généralisent. En 1958, Solal commence à composer l'ambitieuse Suite en ré bémol pour quatuor de jazz, d'une durée d'environ 30 minutes. En 1959, Martial Solal compose sa première musique de film pour Deux Hommes dans Manhattan de Jean-Pierre Melville, ami et admirateur du pianiste depuis sa Suite en ré bémol. Le compositeur principal, Christian Chevallier, était malade et n'a pas pu écrire la dernière séquence de 7 minutes. Solal a donc écrit un petit ostinato au piano d'une dizaine de notes, et une très courte mélodie jouée par Roger Guérin. Pour Solal, « le plus difficile a été de jouer le même riff pendant sept minutes sans aucun effet, sans aucune variation de tempo ou de dynamique. Un vrai test. Melville a apprécié le suspense créé. Sa renommée commence à grandir aux Etats-Unis, berceau du jazz : Oscar Peterson, de passage en France en juin 1963, passe l'écouter au Club Saint-Germain. Le producteur américain George Wein l'invite à jouer pendant deux semaines au Hickory House, un club de la 53e rue à New York, avant de le présenter au Festival de Newport en 1963. Pour Martial Solal, ce fut un choc : aucun musicien de jazz français n'avait été invité aux Etats-Unis depuis Django Reinhardt. Comme il était invité sans son trio, Joe Morgen, l'envoyé de Wein, lui présenta le contrebassiste Teddy Kotick et le batteur Paul Motian, qui jouaient avec Bill Evans ; l'entente entre les trois musiciens est rapide. Le succès est au rendez-vous et l'engagement à Hickory House est prolongé de trois semaines ; Le Temps lui consacre également deux colonnes. Le concert de Solal à Newport est publié (At Newport '63) après quelques « reprises » enregistrées en studio le 11 juillet 1963. L'album est salué par la presse américaine, ainsi que par Duke Ellington et Dizzy Gillespie. Le célèbre producteur Joe Glaser le prend sous son aile et, en une semaine, Solal a tout ce qu'il faut pour s'installer à New York : une carte de sécurité sociale et une carte de cabaret, lui permettant de jouer dans des clubs. . Il lui propose un engagement à la London House de Chicago, lieu de référence pour tous les grands pianistes. Mais Solal, de retour en France, ne retourne pas aux Etats-Unis. Divorcé d'un jeune enfant (Éric Solal), sa situation familiale est trop compliquée pour cette carrière américaine prometteuse. En 1964, il retourne encore jouer sur la côte ouest des États-Unis, notamment à San Francisco, où il rencontre Thelonious Monk. Cette absence de la scène américaine depuis plusieurs années explique en partie le fait que Solal reste encore relativement méconnu outre-Atlantique. En 1960 au Club Saint-Germain, Martial Solal crée son trio avec Guy Pedersen à la contrebasse et Daniel Humair à la batterie. En 1965, Martial Solal crée un nouveau trio avec Bibi Rovère à la contrebasse et Charles Bellonzi à la batterie. En 1970 sort Sans tambour ni trompette, que Martial Solal considère comme son album le plus novateur. Martial Solal a publié plusieurs albums pour piano solo dans les années 1970 : Martial Solal lui-même (1974) ; Plays Ellington, prix « In Honorem » de la Jazz Academy avec distinction (1975) ; Rien que du piano (1976) et The Solosolal (1979). En 1983, Bluesine est sorti par Soul Note. En 1990, il improvise devant le film muet Feu Mathias Pascal de Marcel L'Herbier, exercice qu'il pratique régulièrement. L'album est publié par Gorgone Productions. À partir de 1974, Martial Solal donne des centaines de concerts en duo avec le saxophoniste Lee Konitz, dont plusieurs sont enregistrés et publiés : European Episode et Impressive Rome (1968 et 1969), Duplicity (1978), The Portland Sessions (1979). ), Live aux Berlin Jazz Days 1980, Star Eyes, Hambourg 1983 (1998). Au milieu des années 1970, Solal joue en duo en Allemagne avec le contrebassiste danois Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen. Ils enregistrent un album sorti en 1976 sur le label allemand MPS, Movability. Dans les années 1970, Martial Solal rencontre le compositeur Marius Constant et commence à s'intéresser à la musique contemporaine, qui semble lui offrir de nouvelles possibilités pour le jazz. En 1977, Solal et Constant co-écrivent Stress, pour trio de jazz et quintette de cuivres. Les deux musiciens enregistrent Stress, psyché, complexes en 1981. En 1974 sort Locomotion avec Henri Texier et Bernard Lubat, un disque étonnant et humoristique sur lequel Solal joue du piano et du piano électrique dans un style groovy proche du jazz-rock. Il s'agit d'un regroupement de petites pièces destinées à illustrer des diffusions de séquences sportives à la télévision. L'album a été réédité en 2019 par Underdog Records pour le Record Store Day. En 1980, l'album Happy Reunion, en duo avec Stéphane Grappelli, reçoit le prix Boris-Vian du meilleur enregistrement français. En 1988, 21h/23. Town Hall a été publié, avec Michel Portal, Daniel Humair, Joachim Kühn, Marc Ducret et Jean-François Jenny-Clark. Au début des années 1980, Solal forme un nouveau big band de seize musiciens, dont Éric Le Lann, pour qui il écrit un nouveau répertoire. Cet orchestre se produit dans toute l'Europe, y compris dans tous les pays de l'Est. Il enregistre deux disques, un en 1981, un autre en 1983-84, avec des morceaux ambitieux, dont un qui occupe toute la face d'un disque 33 tours. Il écrit des arrangements de chansons de Piaf et Trenet pour Éric Le Lann, qui figurent sur l'album Éric Le Lann joue Piaf et Trenet (1990). Au début des années 1990, Martial Solal crée le Dodécaband, un « medium band » de douze musiciens qui reprend la structure traditionnelle des big bands : trois saxophones, trois trompettes, trois trombones et une section rythmique. Le groupe donne peu de concerts, et n'est pas enregistré. A l'invitation du festival Banlieues Bleues en 1994, il travaille sur des pièces de Duke Ellington, comme en témoigne l'album Martial Solal Dodecaband Plays Ellington (2000). Avec un nouveau big band qu'il appelle le Newdecaband, Solal publie Exposition sans tableau (2006), composé de compositions originales. Dans ce groupe se trouve la chanteuse de jazz Claudia Solal, fille du pianiste, qui sert d'instrument à l'orchestre. Au début des années 1990, Martial Solal réalise une émission hebdomadaire sur France Musique. Il invite près d'une centaine de pianistes à participer, seuls, à des duos ou des trios, parmi lesquels Manuel Rocheman, Jean-Michel Pilc, Robert Kaddouch, Baptiste Trotignon, Franck Avitabile et Franck Amsallem. Martial Solal improvise pour France Musique, un album sorti en 1994, reprend certaines des improvisations jouées par le pianiste solo lors de ces émissions. En 1995, Martial Solal enregistre Triangle avec un groupe rythmique américain : Marc Johnson (contrebasse) et Peter Erskine (batterie), trio avec lequel le pianiste part en tournée. En 1997, suite à l'album Just Friends, il se produit en Europe et au Canada avec un trio composé de Gary Peacock et Paul Motian, le batteur que Solal connaît depuis At Newport '63. Le pianiste retrouve à nouveau le batteur Paul Motian sur Ballade du 10 mars (1999). En 2002 et 2003, Solal continue de jouer aux États-Unis, à San Francisco, Los Angeles et New York. Mais peu friand de voyages, il annule à la dernière minute le concert prévu au Kennedy Center de Washington en 2005. En octobre 2007, il enregistre Live at the Village Vanguard, son premier enregistrement pour piano solo au Village Vanguard. En 2009, le festival Jazz à Vienne lui offre carte blanche. Il interprète un programme pour six pianos qu'il a composé, Petit Exercice pour Cent Doigts, en compagnie de Benjamin Moussay, Pierre de Bethmann, Franck Avitabile, Franck Amsallem et Manuel Rocheman. Il joue ensuite du deux pianos avec Hank Jones, accompagné de François et Louis Moutin. La soirée se termine par un concert réunissant les cordes de l'Opéra de Lyon sous la direction de Jean-Charles Richard, les cuivres du Nouveau Décaband et le saxophoniste Rick Margitza. En 2015, Works for Piano and Two Pianos est sorti. On retrouve plusieurs compositions de Solal interprétées par Éric Ferrand-N'Kaoua : Voyage en Anatolie, les neuf Préludes Jazz et les Onze Études. Martial Solal rejoint Éric Ferrand-N'Kaoua pour interpréter la Ballade pour deux pianos. Bien qu'il ait déclaré vouloir ralentir son activité compte tenu de son grand âge (il a eu 90 ans en 2017) et suite à des problèmes d'anévrismes, Martial Solal continue de se produire sporadiquement sur scène, notamment en duo avec Bernard Lubat (2014), Jean -Michel Pilc (2016) ou David Liebman (Masters à Bordeaux, 2017, et Masters à Paris, 2020). En mars 2018, est sorti My One and Only Love, un album live solo enregistré en Allemagne. Des histoires improvisées (paroles et musique) (JMS/Pias) sont apparues le 16 novembre 2018, alors que Solal avait déjà annoncé sa retraite. Il est décédé à l'âge de 97 ans, lors de son transfert de Chatou (Yvelines), où il résidait avec sa famille, à l'hôpital de Versailles, le 12 décembre 2024, à 17 heures, comme l'a annoncé son fils, Éric Solal. Style La maîtrise inégalée de l'instrument de Martial Solal s'accompagne d'un talent inépuisable pour l'improvisation. Il est l'un des rares musiciens de jazz européens à avoir eu une réelle influence aux Etats-Unis. Duke Ellington lui-même disait de Solal qu’il possédait « les éléments essentiels d’un musicien en abondance : sensibilité, fraîcheur, créativité et technique extraordinaire ». » Il est « réputé, à juste titre, pour son approche brillante, singulière et intellectuelle du jazz. Le style de Martial Solal est marqué par des ruptures rythmiques et mélodiques, une grande liberté rythmique, harmonique et tonale et une grande virtuosité. Il est très imaginatif, déconstruisant les mélodies, présentant une idée sous tous ses angles, dans une approche presque cinématographique « avec des gros plans, des travellings, des contrechamps, des panoramiques, des contre-plongées… autour d'un thème central ». On pense aussi aux dessins animés - Solal improvise régulièrement un Hommage à Tex Avery - : 'le pianiste rappelle le principe de Gerald Scarfe : chercher jusqu'à quel point on peut déformer un personnage (dans le cas de Solal, un morceau) tout en le laissant reconnaissable.' Il joue régulièrement des standards, qu'il aborde sans aucun plan préétabli : « quand Martial Solal joue un morceau qu'il a déjà joué de nombreuses fois , il n'a pas de version plus ou moins préparée sur laquelle se baser. Il improvise à partir de rien, cherchant à se renouveler sans cesse. » Il peaufine ces morceaux dans tous les sens, ajoutant quelques accords ou procédant à des réharmonisations totales et vastes, masquant la mélodie, ne jouant que des fragments avant de la révéler. Sa virtuosité lui permet d'alimenter son imagination sans limites et d'oser prendre tous les risques2. Cependant, même s'il prend de grandes libertés, il reste proche de la structure et de la mélodie des morceaux qu'il joue. Même s'il a choisi dès le début de créer un style personnel et unique, le jeu de Martial Solal est influencé par des pianistes stride tels que Willie 'The Lion' Smith ou Fats Waller, ainsi que par des pianistes comme Art Tatum, Teddy Wilson ou encore par des musiciens bebop. comme Charlie Parker. Il reconnaît également l'influence de Thelonious Monk, plus dans la conception musicale que dans son jeu pianistique, ainsi que celle de Duke Ellington. Pour Stefano Bollani, il est « le seul pianiste au monde qui n’a pas été influencé par Bill Evans. » Martial Solal a continué à perfectionner sa technique tout au long de sa vie – il se montre également assez critique envers les pianistes qui arrêtent de pratiquer avec l'âge. Martial Solal a publié JazzSolal en 1986, « une introduction complète aux styles de jazz pour piano solo » en trois volumes (Facile, Intermédiaire, Plus Difficile). En 1997 paraît sa Méthode d'Improvisation dont le but est de « familiariser les candidats improvisateurs aux règles de l'improvisation , en leur proposant un travail progressif appuyé par de nombreux exemples destinés à développer leur oreille, leurs capacités rythmiques, mélodiques et sens harmonique ainsi que leur imagination. » Discographie Martial Solal discographie dans Discogs Read the full article

#SMLPDF#noten#partitionmusicale#partitura#sheetmusicdownload#sheetmusicscoredownloadpartiturapartitionspartitinoten楽譜망할음악ноты

0 notes

Text

nobody believes he's real. he tags his tumblr blog with isolated lines from john donne's poem "song". his favorite book is a "middle grade" deconstruction of the fairytale genre. 80% of his wardrobe is black. he's somewhere in between girlfag and boydyke. she's a classically trained ballet dancer. she chose an illegible irish name with three different pronunciations for fun. she considers a dual biography of ulysses s grant and robert e lee light reading. she's seen ducktales 2017 at least 13 times. she's really into bees but only symbolically and for geneological reasons. she's a mormon witch. i could keep going

0 notes

Note

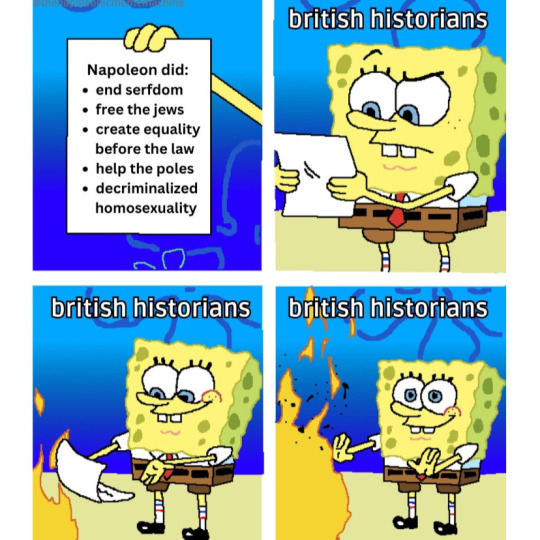

Alright, my brain currently has the consistency of a package of gummi bears left on the floor of Death Valley in summer, but will try to answer two major points of my objection to Roberts' biography of Napoleon.

Let me say first up that I am not a professionally trained historian, and I don't pretend to be. I do, however, read a lot of books. I am trained to critically evaluate texts.

And, to the anon who sent this ask: read more. Read a lot more. Don't just settle for what other people tell you is "THE" book. Settling for what everyone else thinks is definitive is a trap, a shortcut to cultural and historical illiteracy, complacency, and a dearth of curiosity.

In the words of Carl Sagan: "Stay curious."

That being said, his biography on Napoleon is not bad, not by a long shot. There's some interesting tidbits in it that I did like. It's researched and put together well, but one should keep in mind that it was written with an agenda, and should not be treated as a singular source of all things Napoleonic.

One of Roberts' pet topics is the Theory of the Great Man. The Great Man needs no one, the Great Man is a lone genius who does everything by himself, the Great Man can do no wrong (until he does), the Great Man shall not be questioned.

John Donne might have said "No man is an island," but in the Theory of the Great Man, the Great Man is the island.

And you can see this in the way he characterizes Napoleon. His take on Napoleon is someone utterly devoid of compassion and humanity. His relationships with others is not well documented in Roberts' book. In Roberts' estimation, Josephine's death is barely worth noting above pond scum when its mentioned to Napoleon, yet I can recall in other texts where Napoleon showed grief and emotion at death of others such as Lannes, Duroc, and Murat.

No, his friendship with Lannes, his relationships and friendships with his marshals and others, is of inconsequence to Roberts when, in reality, they likely had a massive influence on Napoleon's outlook and day-to-day. He glosses over them quickly.

Roberts focuses largely on Napoleon's military successes (and defeats), while giving lip service to, or not mentioning at all, Napoleon's civic achievements. He glosses over the influence Enlightenment thinkers had on the French Revolution, and therefore the Napoleonic Code and its contemporary use.

(This actually doesn't really come as a shock after learning more about Andrew Roberts, but I will get to that.)

The way I approach a topic is I have to understand all of it. For me, when I approach trying to Napoleon, you have to look at his family dynamics, each sibling's personality, how that impacted Napoleon. You must examine the interpersonal relationships he had with Junot, with Ney, Davout, Fouché etc, and so on so forth. Go back to the beginning, to his life in Corsica, when, as a child, he would have walked past the corpses of people publicly executed for opposing the French occupation. Understand the context of the time and world in which he lived and would have colored his every day life. Peel back the layers of his psychology and dig in deep to figure out what makes him tick.

I take a holistic approach to studying Napoleon. I have to understand all of it, how it all functions. Not just what puzzle pieces look the most interesting. I want to fit the entire puzzle together. So, I choose to read beyond "THE" book everyone is recommending. At some point, when people start hawking one book as "THE" book, it starts feeling like propaganda.

If you want to understand Napoleon, you need to read a lot more than just Andrew Roberts' book. Read the various books on his marshals, for instance, and other figures as well. Understand that each of your sources are going to have their biases and, therefore, you much approach them critically. Every book is going to have an agenda, and you are going to have to read many of them to form your own picture of Napoleon.

Roberts, himself, is ... an issue.

This is a man who excused Winston Churchill's deliberate starvation of up to three million Indians, and glossing over Churchill's racism, when Churchill himself has been quoted as disparaging Indians as "a beastly people" and worse.

Then I dug further down on Roberts.

Roberts is of the opinion is that he wants the British Empire should be presented as both positive and negative. Roberts also believes that British colonialism was beneficial to local populations of the countries occupied by the empire, and that the documentation of atrocities carried out against those populations (like genocide, incarceration, displacement, and worse) makes the empire look bad, and often dismisses what he considers revisionist history pointing that out. He believes these critiques undermine the positive portrayal of Western Civilization.

He's praised Brexit, and Thatcher. He's pro-monarchist. He's a defender of "traditional British institutions and values" whatever the hell that's supposed to mean. He's an unapologetic hardline conservative. He seems to be a believer that the world revolves around Britain, which makes his non-mention of the Napoleonic code make sense, in retrospect.

In my opinion, and my opinion only, which you may disregard, this makes him a fucking dick.

what's wrong with A. Roberts' Naps bio? D: asking because I bought it according to many suggestions stating it was "the one"...

Just blogging this ask for now, as I will answer you in depth later. This pretty much sums up everything wrong with Roberts though, and I’m trying to construct a reply that isn’t full of f-bombs.

If anyone else also wants to reblog and answer the anon, go for it.

#i have slept four hours and have to be awake in another four#fml#andrew roberts#napoleonic era#napoleon's marshals#history#historiography

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nonfiction to look out for in 2022

Nonfiction to look out for in 2022

This article titled “Nonfiction to look out for in 2022” was written by Rachel Cooke, for The Observer on Sunday 26th December 2021 11.00 UTC It’s getting quite hard to ignore the fact that publishers are increasingly hunting in packs, seemingly driven more by trends than by taste. Next year’s nonfiction lists are dominated to an almost ridiculous degree by books about identity and, perhaps…

View On WordPress

#2022 culture preview#Article#Autobiography and memoir#Biography books#Books#Culture#Features#Francis Bacon#Health#History books#John Donne#mind and body books#Music books#Observer New Review#Poetry#Rachel Cooke#The New Review#The Observer

0 notes

Text

I'm still learning fuck all about John Donne from this biography, but it remains far more entertaining than it has any right to be. Today's gem on the history of handshakes:

#Katherine Rundell#Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne#John Donne#sir walter raleigh#handshakes#early modern history

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Of all the fascinating people who came into J. Robert Oppenheimer’s life during his years at UC Berkeley, few are as intriguing — or as tragic — as Jean Tatlock, the woman some believe was the love of his life.

Oppenheimer was 25 when he arrived on the Berkeley campus in 1929 as an associate professor of physics. He moved into 2665 Shasta Road, up the windy, steep hills that flank the university. From the windows, he could see the bay.

The Shasta Road property was always lively. In the main house, Oppenheimer’s landlord Mary Ellen Washburn hosted constant parties; intellectuals roved in and out of the property, debating ideas and drinking late into the night. Oppenheimer objected to teaching before 11 a.m. so he could stay up chatting and smoking.

In the spring of 1936, Oppenheimer met a young woman named Jean Tatlock at one of these parties. He already knew her father, an acclaimed Berkeley professor of Old English; professor John Tatlock enjoyed having lunch with Oppenheimer at the Faculty Club, where Oppie, as he was known around campus, showed off his wide-ranging knowledge of literature and ability to recite passages from memory.

Jean was 22 and brilliant. She was in her first year at Stanford Medical School, studying to be a psychiatrist. This, of course, was highly unusual for a woman in the 1930s, and Tatlock made an impression. Friends and acquaintances recalled she was the type of person everyone noticed when she walked into a room. (Florence Pugh was cast as Jean Tatlock in Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” movie.)

#OPPENHEIMER will have its French premiere on July 11th at the Grand Rex in Paris. pic.twitter.com/W0o25gL6cy

— Florence Pugh Photos (@pughphotos) June 29, 2023

Oppenheimer, who loved sharp, unconventional women, fell fast. By the fall, the pair were an item, and something of an intellectual power couple. Oppenheimer was the star of the physics department, luring talent from all over the nation to join him. Tatlock was a trailblazing psychiatrist who delighted Oppenheimer with her love of poets like John Donne. “All of us were a bit jealous,” one friend recalled in “American Prometheus,” the definitive Oppenheimer biography.

Their relationship, though, was a tumultuous one. Tatlock went through periods of deep depression, and Oppenheimer was often the person who talked her through them. When she was low, so was he. “American Prometheus” detailed how Robert Serber, a nuclear physicist who met Oppenheimer at Berkeley and became one of his closest friends, watched their relationship unfold.

“He’d be depressed some days because he was having trouble with Jean,” Serber said.

Over the course of three years, they got engaged at least twice, broke things off and kept getting back together. Serber said Tatlock would cut contact with Oppenheimer for weeks or even months. When she returned, Serber said she would “taunt him about whom she had been with and what they had been doing. She seemed determined to hurt him, perhaps because she knew Robert loved her so much.”

In retrospect, it seems clear at least some of this tumult was due to Tatlock’s struggle to understand her own sexuality. In letters to friends, she expressed fear that she might be attracted to women. The thought tormented her — she was then a student of Freudian psychiatry, which maligned homosexuality as a mental defect. Torn between her genuine love for Oppenheimer and her anguished confusion, Tatlock called things off for good in 1939. A year later, Oppenheimer’s new love, a married woman named Kitty Harrison, became pregnant with his child. Her husband agreed to a divorce, and Harrison and Oppenheimer married in 1940.

When a friend asked Tatlock if she regretted not marrying Oppie, she said she did. Maybe she would have married him if she wasn’t “so mixed up,” Tatlock lamented.

But their relationship did not end — and their affair would have profound implications for both of them.

---

Between 1939 and 1943, it’s believed Oppenheimer continued seeing Tatlock several times a year. They still went to parties together in Berkeley, and at least once they got drinks at the Top of the Mark. When she was feeling low, she’d call Oppie and he’d talk to her for as long as it took to see her through the dark moment. In early 1943, he left for Los Alamos to head the Manhattan Project. No one could know the details of his work in the New Mexico desert. Oppenheimer left Tatlock without saying goodbye.

For Tatlock, who relied on Oppenheimer for support, this was a devastating abandonment. He couldn’t explain what had taken him away, and she wrote him pleading letters. By then, she had become a doctor at Mount Zion Hospital in San Francisco (today, it’s part of the UCSF campus). It was an incredible feat of determination in the male-dominated field, but despite her professional success, loved ones knew that Tatlock was not well.

On June 14, 1943, Oppenheimer flew from Los Alamos to see her. Unbeknownst to him, he was being tailed by military officers. In their report to the FBI, they said they watched Oppenheimer take the train from Berkeley to San Francisco, “where he was met by Jean Tatlock who kissed him.” They went to Xochimilco, a Mexican restaurant on Powell and Broadway, and had dinner and drinks. Then, they went back to her top floor apartment at 1405 Montgomery St., a pretty block tucked right underneath Coit Tower. With the spies watching from the street below, the lights went out at 11:30 p.m.

The next morning, Oppenheimer emerged from the flat. They had one last meal together at Kit Carson’s Grill before Tatlock drove him to the airport. He hopped a flight back to New Mexico, and she went home. Soon, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had a report about their meeting in his hands.

Both were already on his radar. For much of Tatlock’s adult life, she had been a dues-paying, meeting-attending communist. She even wrote for the Communist Party’s official West Coast publication, the Western Worker. Hoover, with his characteristic paranoia, became convinced Tatlock might be passing nuclear secrets to the Soviets. “It has been determined that Jean Tatlock … has become the paramour of an individual possessed of vital secret information regarding this nation’s war effort,” Hoover wrote in a memo. He had the phone in Tatlock’s Montgomery Street apartment tapped.

There is no evidence Tatlock was any sort of spy, or that she even knew what Oppenheimer was doing at Los Alamos. In 1954, when Oppenheimer was interrogated over accusations he was a Communist sympathizer, he was asked why he flew to see Tatlock in 1943. “Because,” he answered, “she was still in love with me.”

Tatlock’s mental health deteriorated further in the months after their meeting. Around the start of the new year 1944, Tatlock stopped answering her phone. Fearing the worst, her father drove to her apartment on Jan. 4, 1944. He had to climb through an open window to get inside. There, he found his daughter in the bathtub. Jean Tatlock was dead. She was just 29.

Immediately after finding her, her father did an odd thing: He lit a fire and burned her letters and photos. A few hours later, he finally called a funeral parlor. That funeral parlor called police, who arrived at 1405 Montgomery to find a dead woman and a pile of burned paper. Although no one now living knows what those items were, many historians believe it may have been evidence that Tatlock was lesbian or bisexual.

Much has been made of the unusual circumstances of her death over the years, particularly because an autopsy found she’d eaten a full meal before dying. Some believed she was murdered by the government. But Tatlock left a handwritten suicide note and endured a lifetime of clinical depression, so most who knew her best did believe she ended her own life.

Sequestered at Los Alamos, the Serbers received a cable from Oppenheimer’s former landlady at Shasta Road. It informed them that Tatlock had died the day before. Robert Serber rushed to find Oppenheimer and break the news to him before someone else did. He was too late. “Deeply grieved,” Oppenheimer went for a long, solitary walk in the hills surrounding Los Alamos.

“Jean was Robert’s truest love,” Serber said. “He loved her the most. He was devoted to her.”

Tatlock’s family had her remains sent to Albany County, New York, where she was buried in the family plot. Her stone is simple. It reads:

Jean Frances Tatlock 21 February 1914 4 January 1944

---

In 1962, Gen. Leslie Groves, the military leader of the Manhattan Project, wrote to Oppenheimer asking why he had named the first atomic bomb test “Trinity.”

“Why I chose the name is not clear, but I know what thoughts were in my mind,” Oppenheimer replied. “There is a poem of John Donne, written just before his death, which I know and love.”

The poem he quoted was called “Hymn to God, My God, in My Sickness.”

I joy, that in these straits I see my west; For, though their currents yield return to none, What shall my west hurt me? As west and east In all flat maps (and I am one) are one, So death doth touch the resurrection.'

#Oppenheimer#Jean Tatlock#Florence Pugh#American Prometheus#John Donne#Leslie Groves#Hymn to God My God in My Sickness

35 notes

·

View notes